The use of aversive conditioning in cougars (Puma concolor) in the mitigation of anthropic conflicts and their challenges

- GEAS Brasil

- Aug 10, 2025

- 7 min read

The conflict between humans and free-living animals is a limiting factor and a great challenge in the conservation of several large endangered carnivores, as already recorded for tigers (Panthera tigris) and lynx (Lynx lynx), for example (Barlow et al., 2010; Graham et al. 2005). Historically, lethal control strategies are predominant. In lethal control occurs the elimination of animal specimens aiming at population control or reduction of social tension generated by the conflict (Lorand et al., 2022). This method has already been associated with the eradication of populations or even species from certain areas (Nyhus, 2016). Carnivores play an essential ecological role in shaping the composition and structure of landscapes, through the regulation of herbivorous animal populations and their impact on vegetation (Lorand et al., 2022). Thus, in order to avoid the loss of human and animal lives, as well as mitigate impacts on plantations, livestock and properties, non-lethal intervention methods have been prioritized (Nyhus, 2016). The adoption of aversive conditioning for predators, in an attempt to increase the fear of humans, is a possibility of non-lethal management. In addition to these techniques, the use of fences, alarms and gas explosives can also be tactics for scaring or limiting access of these predators in certain properties or locations (Lorand, 2022). Therefore, a study by Parsons and collaborators (2024) evaluated the effectiveness of aversive conditioning in brown jaguars (Puma concolor) through the use of hunting dogs. It is necessary to consider that the use of hunting dogs is a controversial and challenging approach (Dellinger, 2023), however, it may be an alternative to be applied in areas with history of human-wild interface conflicts as replacement for lethal control strategies. The technique used, called "Hazing", is characterized by practices that aim to teach free-living animals to stay away from humans (Munson, 2025). It aims to construct a negative association between an initial stimulus and a painful aversive stimulus (such as the use of paintball balls) or stressful (such as hunting dogs), so that such initial stimulus elicits a fear response (Blumstein, 2016).

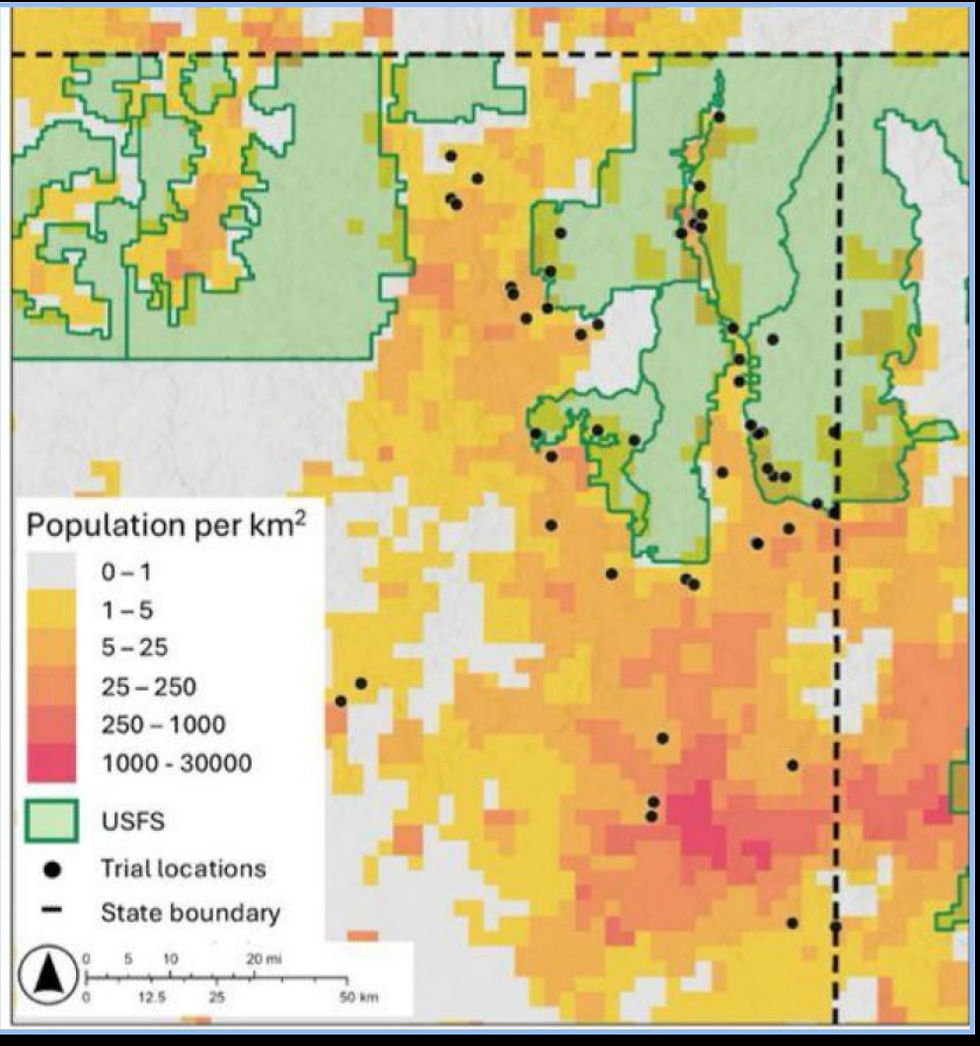

The study area covered the northeastern region of Washington (USA), in which conflict with brown jaguars represents a chronic problem. In the period from November 2019 to March 2024, animals over 2 years of age located near areas of human occupation were captured and given a collar with two GPS devices and earrings for identification. These animals were divided into a control group (n = 12) and a treatment group (n = 29), and all individuals were exposed to the human approach, but only the treatment group was exposed to the subsequent action of the hounds.

Caption. Map of the area where the study was conducted, showing: human density (in population per km 2), the location of each ounce at the time of the first approach (black points) and the boundaries of the US Forest Service (USFS - U.S. Forest Service boundaries). The upper black dotted line indicates the border between Washington - USA and British Columbia - Canada, while the right side line indicates the border between Washington - USA and Idaho - USA. Credits. Mitchell Parsons - article "Evaluating The Efficacy of Aversive Conditioning of Mountain Lions with Hounds" figure 1.

The human approach phase began about 400 m away from an identified jaguar. The team played a podcast with conversation from a group of people at 80 dB volume while approaching the animal at constant speed. During this approach, the distance between the observer and the animal when it began to move was measured via GPS, calling it FID (from the English "flight initiation distance" whose free translation is "initial flight distance"). As soon as the movement of the animal began, the monitoring phase was established, in which the distance that the animal moved was measured until it stopped for 30 seconds. In the treatment group, this marked the beginning of the hazing phase with the addition of hunting dogs trained to drive away jaguars. As soon as the predator was away, human observers quickly approached the area to collect the dogs. It is noteworthy that in the first phase of Hazing paintball weapons were used as initial painful stimulus.

At the end of the research it was concluded that the jaguars in the treatment group showed greater aversion to the approach of observers, and the FID increased throughout the tests. It should be noted that in the control group the animals were accustomed to this approach with a considerable reduction of FID, which suggests that in the absence of an aversive stimulus the animals can gradually become accustomed to human presence. These results suggest that the use of hunting dogs as aversive stimulus can be an alternative to control conflicts between humans and brown jaguars, provided it is a regulated and properly planned practice. However, it is of paramount importance to consider that the study does not investigate the physiological consequences (such as myopathies of capture and problems arising from the chase process) and ecological (such as the introduction of dogs and their possible pathogens in the wild environment, for example) of the technique employed in individuals and their ecosystem, as well as does not evaluate long-term results.

A literature review conducted by Lorand and collaborators (2022) sought to evaluate the efficiency of different interventions for the management of conflicts between humans and large carnivores. The effectiveness of the methods was evaluated according to three criteria, one of them being the negative side effects caused. These effects were subdivided into damage to the population of large carnivores, including possible damage to the life and integrity of individuals and the viability of the entire population, and damage to cohabitation, considering economic damages and impacts on human tolerance. Although non-lethal interventions present low potential for harm (average = 6.0/100, the limit being = 20.0/100), the authors highlight disparities in the level of reliability of the analyzed works, mainly regarding the protocols used and the lack of rigorous experimental projects. The studies analyzed, as well as that discussed in this text, did not follow the changes in conflicts and the potential damage to the carnivorous population in the long term, making it impossible to fully assess their effectiveness and ethical aspects. In addition, it is necessary to consider that guard dogs were responsible for the hunting and killing of target and non-target species on several occasions (Lorand et. al, 20222). However, when properly trained and corrected, they are able to discriminate the species minimizing accidents, including with herbivores (Whitehouse-Tedd et. al., 2020).

According to Khorozyan and Waltert (2019), the effectiveness of anti-predator interventions tends to decrease over time as animals become accustomed to them. When analyzing research to measure how long interventions against predatory animals remain effective, the authors concluded that in most cases the use of guard dogs resulted in rapid habituation, causing a drop in efficiency after one month or year. Despite being classified as a non-lethal technique, the pursuit by guard dogs can generate lethal or sub-lethal consequences for wildlife in the long term, such as ecological and physiological impacts of fear, population displacement and injuries that result in reduced physical fitness and mortality (Whitehouse-Tedd et al., 2020). Allen and colleagues (2019), propose that the negative consequences on animal welfare may be potentially greater with the use of guard dogs when compared to lethal methods. However, according to Johnson and colleagues (2019), the use of guard dogs is efficient in reducing conflicts requiring minimal interaction with wildlife, while lethal methods are based on the substantial reduction of wild animal populations, causing high mortality rates and impacting on the behavior of more animals. Thus, non-lethal methods remain the most efficient and ecologically ethical, but still need more discussion and standardization, not only of their application form, but also of the monitoring of their short-term to long-term effects. In a perspective of the Brazilian reality, dogs may not be the most indicated non-lethal control methods for human-animal conflict prevention. However, other techniques can and should be studied so that such conflicts are mitigated in order to protect the population, agricultural production and animals themselves.

Author: Giovanna de Melo Inácio - Deputy Director of Dissemination of GEAS Brazil.

August/2025 Wild Panel.

References:

ALLEN, B. L.; ALLEN, L. R.; BALLARD, G.; DROUILLY, M.; FLEMING, P. J. S.; HAMPTON, J. O, HAYWARD, M. W.; KERLEY, G. I. H.; MEEK, P. D.; MINNIE, L.; O’RIAIN, M. J.; PARKER, D. M.; SOMERS, M. J. Animal welfare considerations for using large carnivores and guardian dogs as vertebrate biocontrol tools against other animals. Biological Conservation. v. 232. p. 258-270. 2019..

BARLOW, A. C. D.; GREENWOOD, C. J.; AHMAD, I. U.; SMITH, J. L. D. Use of an action‐selection framework for human‐carnivore conflict in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Conservation Biology. v 24, n 5, p 1338–1347. 2010.

BLUMSTEIN, D. T. Habituation and sensitization: new thoughts about old ideas. Animal Behaviour. v. 120, p. 255–262. 2016.

DELLINGER, J. A.; BASTO, A. F; VICKERS, T. W.; WILMERS, C. C.; SIKICH, J. A.; RILEY, S. P. D.; GAMMONS, D.; MARTINS, Q. E.; WITTMER, H. U.; GARCELON, D.K.; ALLEN, M. L.; CRISTESCU, B.; CLIFFORD, D. L. Evaluation of the effects of multiple capture methods and immobilization drugs on mountain lion welfare. Wildlife Society Bulletin. v. 47, e. 1494. 2023.

GRAHAM, K; BECKERMAN, A. P.; THIRGOOD, S. Human-predator-prey conflicts: ecological correlates, prey losses and patterns of management. Biological Conservation. v. 122, p. 195-171. 2005.

LORAND, C. ROBERT, A.; GASTINEAU, A.; MIHOUB, J-B; BESSA-GOMES, C. Effectiveness of interventions for managing human-large carnivore conflicts worldwide: scare them off, don’t remove them. Science of The Total Environment. v. 838, 156195. 2022.

MUNSON, P. To Chase or Not to Chase: Hazing Mountain Lions with Dogs. Mountain Lion Foundation. 2025. Disponível em: https://mountainlion.org/2025/01/14/to-chase-or-not-to-chase-hazing-mountain-lions-with-dogs/. Acesso em: 7 jun, 2025.

NYHUS, P. J. Human–wildlife conflict and coexistence. Annual Review of Environment and Resources v. 41, p. 143–171. 2016.

PARSONS, M. A.; GEORGE, B. E.; YOUNG, J. K. Evaluating The Efficacy of Aversive Conditioning of Mountain Lions with Hounds. CWBM. v. 13, n. 2, p. 126-137. 2024.

KHOROZYAN, I.; WALTERT, M. How long do anti-predator interventions remain effective? Patterns, thresholds and uncertainty. Royal Society Open Science. v. 6. 2019.

WHITEHOUSE-TEDD, K.; WILKES, R.; STANNARD, C.; WETTLAUFER, D. CILLIERS, D. Reported livestock guarding dog-wildlife interactions: Implications for conservation and animal welfare. Biological Conservation. v. 241. 2020.

Comments